i/o (input/output) is pretty much any operation that requires getting data from outside of your computers RAM. (Usually means getting stuff from your hard drive, or over a network.) Hard drives and networks are physical things which need to be accessed, and as such they are extremely slow relative to running computations, or accessing things from your blazing fast RAM. The performance of an i/o bound task is dependent on the devices and interfaces between you and the resource you want to access. This could be kilometers of copper wire maintained by pigeons, or it could be your uber-fast SSD.

Cpu bound operations are operations that are difficult to compute. Not difficult in terms of complexity, but in terms of time and effort required by your cpu to complete the operation. Every operation uses some cpu, but for the most part take such a short time that they don't need to be considered. If your task's performance is dominated by the performance of your cpu, and the task isn't performing as well as you'd like, then the task is cpu bound. Calculating large Fibonacci numbers is the ye olde example of a cpu bound task. The performance of a cpu bound task is dependent on the performance of...your cpu!

This one can be tricky for new people. What does it mean for something to be "blocking"? Computer programs at their most basic (one process, one thread) can only do one thing at a time. Be that some simple addition (1+1) or an abstraction of many operations, like running a function. If you run a cpu bound function that takes a long time, you can consider it "blocking" in that it's taking so long it's stopping other tasks from running and slowing the desired speed of the program. Likewise, if you send a request to a website, you have to wait on the response before you proceed to use the response data. Here your program is "blocking" on network i/o, doing nothing but waiting.

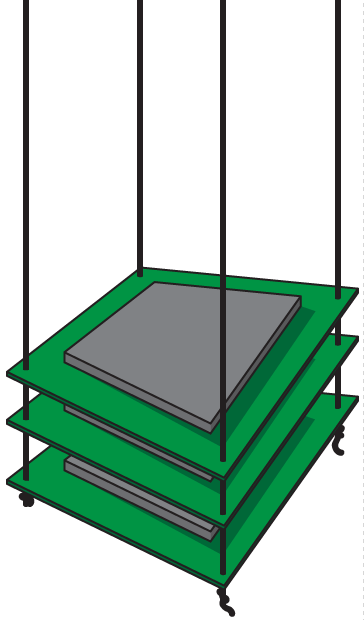

Tasks running under parallelism can do work at the same time, in the most literal sense. This is why having multiple cores in a cpu is useful. If one is busy, another can simultaneously do work.

Concurrent tasks are tasks that are active at the same time. They do not necessarily have to be able to do work at the same time. Concurrent tasks can start, run and end during the running of other tasks they are concurrent with. For the purposes of this page, we will say concurrency does not involve parallelism.

In this fashion, humans are concurrent creatures. Were you to make coffee and a sandwich, you might start the coffee task by boiling some water. While you wait you can start and finish the sandwich task; coming back to the coffee task when the rest of the brewing process is ready to continue.

A coroutine is a function or method which can yield control during its operation back to its caller, remaining in a suspended state until resumed.

An event loop is some code that controls the starting, running and scheduling of other code (usually coroutines) over a program's lifetime. To put it in the words of a friend "well, an event loop is something that handles events in a loop". Obvious, redundant, yet still worth thinking about.

Note: it is a coroutine that decides when to give control back to an event loop. This is different to threading in that thread execution is decided entirely by the thing managing the threads (usually your operating system).

Threading is good for solving i/o blocking. It is the most common way of adding concurrency to python programs. A python program by default has a main thread which runs synchronously, meaning it just runs operations as it needs, one at a time. When you create a new thread, you are creating another thread that runs concurrently with all other threads in the process. The main python thread, and any new threads we make, all run in the same process. A thread cannot do anything if another thread is doing something, and so on. It is a common misunderstanding to think threading adds parallelism.

Because waiting on i/o blocking is pretty much just sitting idle until the i/o access is ready, it's ok to leave one thread waiting on i/o and do cpu bound work in another, coming back to the thread waiting on i/o later.

It is very important to note that threads may switch at any time, as governed by your operating system. You cannot rely on threads to switch at any particular place. Threading can create race conditions.

Because cpu bound work is also in a sense "blocking", doing cpu bound work in two threads simply means switching to and fro between these threads, with no gain in overall speed whatsoever. (In fact, the small overhead of working with threads makes it slightly slower!)

Multiprocessing is good for bringing parallelism to cpu bound tasks. Multiprocessing can also solve i/o blocking, but because the overhead of creating and communicating between processes is so much greater than with other methods it is pretty much always faster to use something else to solve i/o blocking. Multiprocessing is best used when you need to parallelise cpu bound tasks where even with the added overhead, you save time compared to running the same tasks in one process. How do you know when it's worth it? Well, from experience and (more importantly) testing!

Say you have to calculate something that takes 10 seconds per run, twice. In a single process, this will take 20 seconds. In two it will take 10 seconds + the overhead of multiprocessing. Even if you were passing giant blocks of data between the processes, taking a full second, you'd still pretty much cut the time taken in half. (In reality, your time overhead from multiprocessing should be very short.)

Generally you want to ensure the result of the cpu bound task is as small as possible so the overhead of inter-process communication is low. Passing large objects between processes is slow and involves stuff like pickling. Yuck.

Using multiprocessing can (and usually will) create race conditions, which you must manage.

Async is good for doing concurrent i/o. Async confuses the absolute piss out of people; however as a very general concept it's quite simple. An event loop manages tasks (coroutines), and these tasks can be paused during their operation - say, when they want to wait for a network i/o response - yielding control to the event loop, which then allows some other task to run, coming back to the task doing i/o bound work when the i/o is ready. All of this takes place in one thread.

It is very much like threading but rather than create new threads we create new tasks, and rather than have python's guts manage where and when the threads yield control to other threads, the event loop manages which tasks to run and the tasks themselves decide at which points they will allow control to be yielded to the event loop.

A nice side effect of this single threaded concurrency is that it is much harder to create race conditions. The overhead of running an event loop is also usually lower than that of running multiple threads, so pound for pound async is faster than threading. These methods excel at extremely high levels of concurrency.

There are libraries like Twisted that are in some ways very similar to asyncio, requiring managing things like futures and so on. There is nothing wrong with them, but you probably wouldn't like to use them :)

These are basically magic for doing concurrent i/o, built before python had async/await. They are complete voodoo and were created by a group of mimes from the Himalayas during a night of fever dreams. Work bloody great though. They are as battle-tested as any of them, and though they require some unique mechanics to work, generally speaking the resulting code is quite clean and manageable, perhaps even more so than any other method here.

Internally their workings are extremely similar to the previously mentioned async/await style async, but like I said, it's voodoo.